The target audience of the Dara Institute’s Family Action Plan (PAF) are families with very low or zero income, precisely the group most vulnerable to the impacts of an economic crisis. In Brazil, this group accounts for 5.7% of the population, according to World Bank criteria.

Income generation is one of the five pillars of the PAF — the others are Health, Education, Citizenship and Housing. When combined these areas allow the families served to become the protagonists of their own lives. Everyone’s life changes when just surviving for the next meal is no longer a problem, and the quality of life improves. You can buy hygiene and cleaning items, school supplies and even think about home improvements.

The COVID-19 pandemic drove one in four Brazilians below the poverty line in 2020, a number equivalent to almost 51 million people. Without emergency government aid, that already catastrophic number would have risen to 67 million.

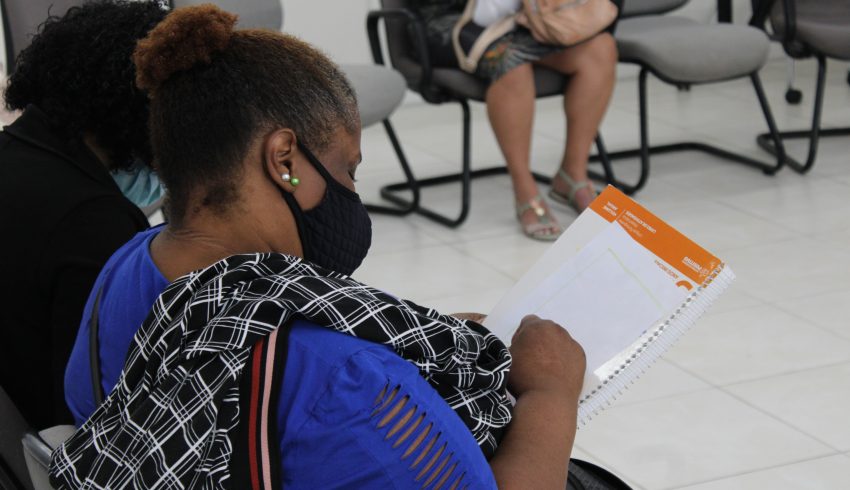

In this scenario, improving a family’s income is to start a cycle of prosperity. When the family in a vulnerable situation arrives at the Dara Institute, it is most often represented by a black woman (88%); single mothers with several children — and often some with health problems — without having completed either elementary or high school.

Income generation: more than a financial issue

With more than 30 years of experience in assisting families in extreme vulnerability, the Dará Institute discovered that stimulating income generation and entrepreneurship in these cases is much more than a financial issue.

The person responsible for the family during care is often trapped in a generational cycle in which the future and perspective are unknown words, as if they were not a right. Grandparents lived like this, parents lived like this and so these family heads survive in the same way. Before getting a job or opening a business, they need to discover that they can indeed be a protagonist of change.

One of the main barriers that our team needs to be able to overcome is the low self-esteem among many in this demographic group. One of the most common scenarios at Dara is one related to the first screening: women with low education and many children to raise tend to arrive at Dara with difficulty understanding their place in the world and that they have rights, whether at home, in the community, or in the city where they live, and the power they actually have to break the cycle of misery of previous generations. There are many cases in which women have been physically abused by their husband or partner and does not receive any positive stimulus for what she does at work and at home raising children. It is very common for them to ask: “Am I really capable?”

The first step in the Income sector is to discover the vocation of the person served. Most of the time a mother is living on government benefit programs or is looking for a job. The main intended functions are cleaning services, gardening, porters in buildings and condominiums, beauty and kitchen services.

But what is this person capable of doing to truly transform his/her life? The objective is to facilitate access to new job opportunities based on their talents and dreams and, if necessary, to guide them so that they have all the conditions to open their own business in the creative community economy.

Talents put into practice

Dara Institute offers its own courses in the areas of cooking, beauty and crafts and works with a network of partners who provide places on courses in the most diverse professions.

The woman who used to do braids in the community and received R$5, can learn the practical techniques with us to do her work with quality, charge for it and believe in her potential. The talent for braiding becomes a real job and is worth up to 600% more in terms of income.

Another example is the woman who cooks well, has never been valued. At Dara she can learn to scale up production with what she has at home. Or the one who was someone’s dealer. In the gastronomy course, she can learn to make her own snacks and thus bolster her income. But this is not all. The course offered lasts up to seven weeks and has several modules, such as confectionery, functional gastronomy and sustainable cuisine.

The courses increase the chances of a good cook, with a practical problem to solve — to increase the family’s income —, to develop new talents in the area. In addition to snacks, she can sell cakes, fine biscuits, chocolate eggs at Easter and Panettone at Christmas.

Due to the difficulty getting formal jobs, entrepreneurship is for many families the way to generate income. In the entrepreneurship course, they learn, for example, how to price their products and advertise their point of sale. Value your work and, with that, generate income. It doesn’t matter if she has a tent stretched out over her door or works from home due to the lack of a commercial outlet.

When the person assisted discovers their role, the cycle of vulnerability is broken. The impacts on this woman’s family income and self-esteem are crucial, as everyone’s life at home improves as a result.

What makes it difficult to change the scenario for vulnerable families?

The main public served by Dara, black and brown women, are twice as vulnerable in Brazil in terms of employment and income. An IBGE study on social inequalities, released in 2019, points out that women received, in 2018, 78.7% of the amount of men’s earnings. Black and brown people suffered even more from inequality, receiving 57.5% of white people’s income. If the extremes of inequality are placed side by side, the reality is even starker: black and brown women received only 44.4% of the income of white men. The same survey shows that blacks and browns are just over half of the country’s workforce (54.9%), but they receive far fewer opportunities, making up 64.2% of the unemployed and 66.1% of the underutilized. Even in the informal gig economy, the racial profile is significant: while 34.6% of whites were in informal jobs, the percentage of blacks and browns was 47.3%. These are numbers from 2018, but unfortunately they vary very little in the historical series.

In addition to the unemployment rate, which has stabilized in the double digits since 2016 — reaching a plateau between 10% and 14%, according to IBGE data — three indices have pushed Brazilians into poverty: rising inflation, falling incomes and deteriorating social inequality.

High Inflation:

the recent rise in inflation, mainly observed during 2021, has particularly affected the poorest population. Between January 2021 and January 2022, for example, inflation tripled for the population with very low incomes. This is because food, the main villain in the index during this period, corresponds to most of the expenses of the most vulnerable families. In total, the accumulated IPCA in the last 12 months is 10.54%, an annual figure only comparable to the worst periods after the Real plan in the early 2000s, and in 2015, when it also exceeded double digits.

Falling Income:

While prices rose, Brazilians’ incomes plummeted to historic levels. In the same period, between January 2021 and January 2022, average income dropped by almost 10% to the lowest figure since the IBGE started the PNAD historical series in 2012. The drop in the index has been vertiginous since September 2020, when the government cut the emergency aid distributed during the COVID-19 pandemic in half. This is just an average, but, once again, the poorest suffer the most.

Deepening social inequality:

In addition to the fall in average income and rise in inflation, there has been an equally historic escalation of social inequality indices. The main metric is the Gini Index, a mathematical model that calculates the gap between rich and poor. After a continuous rise since the end of 2014, inequality in Brazil reached the highest point in the historical series in 2019 at 0.489. At least until the outset of the pandemic, when the Gini Index soared again, reaching a record 0.674 in the first quarter of 2021.

The Gini Index is actually usually shown as a figure between 0-100 – so 48.9 and 67.4